Imagine a vast open prairie of rolling hills scattered with wildflowers and grass with the occasional pine and hardwood outcroppings. Would you believe that this is what the South used to look like? Centuries ago, our part of the country consisted exclusively of grasslands.

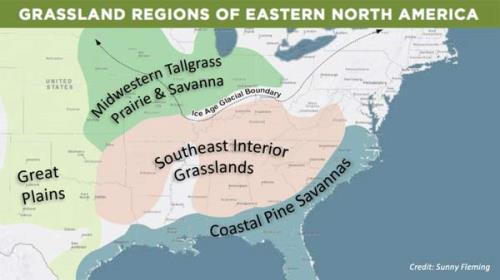

Although “grasslands” brings to mind the Great Plains of the western US, a few hundred years ago, the Southeast had its own great plains–one arguably more attractive than the West’s– adorned with its native flora and fauna. Explorer Ruben Ross wrote in 1812 on his expedition through central Tennessee, “It would be difficult to imagine anything more beautiful. For as far as the eye could reach [the grasslands] seemed one vast deep green meadow adorned with countless numbers of bright flowers springing up in all directions, only a solitary tree and only now and then a post oak were to be seen. It was here that the strawberries grew in such profusion as to stain the horses a deep red color.” Southeastern grasslands covered nearly one-third of the United States, contained roughly by the Ozarks to the west and by the Ohio River to the north. Historically speaking, savannas (grassy plains with few scattered trees) were the most common form of southern grasslands and made up the majority of the Southeast.

Since the early 1800s, the Southeastern Grasslands have been constantly degraded with only about 1 percent of the grasslands remaining. This is the result of countless years of introducing non-native species (such as kudzu and cogon grass), fire suppression (ways to prevent and control wildfires), and constant industrial development. Americans branching out and moving away from the original 13 states began the great decline of the Southeastern Grasslands. As more Americans began to expand, so did development. This meant that more trees were cut and natural ground was cultivated. Soon, much of the previously existing grasslands had been transformed into cities, farms, and grazing lands, destroying soil health and the local ecosystems. Furthermore, as civilization progressed, so did technology, and fire suppressants became popular to protect the newly created cities and towns on the grasslands – a problem because wildfires were an essential factor in the health of the ecosystem due to their ability to regulate density of native trees.

To some people, the items listed above (technology, the construction of cities, etc.) sound like progress, but in reality, such “advancement” comes at a great cost. The Southeastern grasslands were not only a sight to see but also served as an ecological safe haven. Hundreds of native species that used to call the Southeastern grasslands home are now gone, including many native grass species. Without these, the Southeast’s soil health has drastically decreased. Compared to the non-native grasses (introduced because of lawns) that now rule the Southeast, native grasses protect the soil from erosion and help to store nutrients in the soil with roots up to 6 feet deep. Now, much of the Southeastern United States suffers from erosion, sandy or hard clay soil, lack of species diversity, and the loss of its long-forgotten landscape without these native flora and fauna, drastically decreasing the entire ecosystem’s health and resilience.

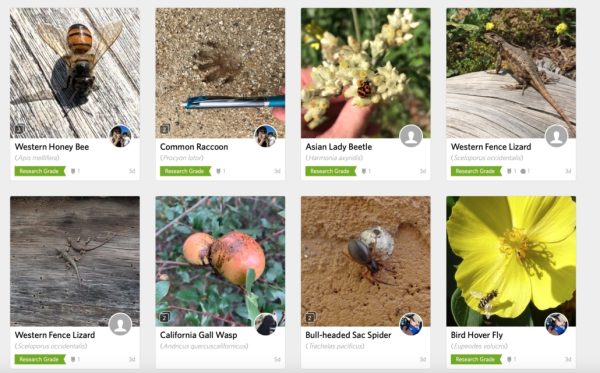

Although most of the damage done to the grasslands is irreversible, modern conservation groups like the Southeastern Grasslands Initiative (SGI) are working tirelessly with volunteers and the government to re-establish the grasslands. Through controlled burns and the re-introduction of native species to the areas they work in, the SGI can bring back high levels of biodiversity and soil health. Conservation work is not the only answer, however. It is also important to have government departments use legislation to actively protect the grasslands from degrading further. Even citizens can partake in activities to help re-establish the grasslands. The SGI offers a wide range of volunteer opportunities for people interested in making a difference. Another way to help is through a mobile app called I-naturalist, which takes your photos of plants and animals, identifies the species, and then uploads the location (with permission) to a wide range of servers to help keep conservation and government groups informed as to what is happening ecologically in different parts of the world. With the help of these private and governmental organizations and involved citizens, there is hope that future generations will one day be able to enjoy and experience the Southeast the way it used to be.